Facebook Political Advertising Transparency Report

Sarah E. Bolden, Dr. Brian McKernan, and Dr. Jennifer Stromer-Galley

Syracuse University

5 October 2020

Note: All screenshots were taken on 5 October 2020. Ad Library Report data was downloaded on 5 October 2020 and contains data on ads that have run between 7 May 2018 and 3 October 2020.

Campaign advertising is predicted to break spending records this election cycle. Online, advertisers have already spent over $605 million running ads on Facebook and Google alone, while total digital advertising for the 2020 presidential election cycle is projected to reach at least $1.82 billion.

The importance of analyzing digital campaign advertising in particular is punctuated by heightened concerns about unethical and/or illegal online advertising behaviors, from the spread of misinformation, to spending by dark money groups, or the possibility that foreign actors may seek to interfere in the election cycle.

Journalists and researchers have cautioned that Facebook does not provide the type of data availability and transparency that is required to provide comprehensive reporting on campaign advertising.

Facebook’s Ad Library was created to store copies of ads that are purchased and run on Facebook and Instagram, and to make this information more accessible and transparent to the public. Since its inauguration in 2018, the Ad Library has been embroiled in controversy: the library’s use-value to journalists and researchers has been mitigated by widespread bugs; the library makes available limited data; and the policies on campaign advertising are weak, which limits the ability to regulate dark money spending and the circulation of misinformation.

This report summarizes the challenges and concerns that the Illuminating project’s team encountered when using Facebook’s Ad Library to conduct research on the 2020 U.S. presidential election. After introducing and contextualizing the Illuminating project and Facebook’s Ad Library, we review three critical problems that we encountered:

1. Advertiser data lacks systematicity and is difficult to reliably retrieve using the Ad Library’s platform and API.

2. There are patterned absences and inconsistencies in the Ad Library’s information, documentation, and data.

3. Facebook’s Ad Library policies lack clarity, and there is limited information available about ads that are removed for policy violations.

We provide examples of each problem and explain why hindering the transparency of the online campaigning ecosystem poses a threat to campaign advertising research by academics and journalists. Our report concludes with recommendations that would help make Facebook’s Ad Library more accessible and transparent to journalists, researchers, and the general public.

Context

Illuminating

Illuminating is a computational journalism project that provides journalists with comprehensive data on the content and character of digital campaign messaging. Illuminating has two interactive dashboards that journalists can utilize. The project’s Campaign 2016 dashboard analyzes Facebook and Twitter content that the 2016 U.S. primary and general election candidates have produced. The Campaign 2020 dashboard classifies Facebook and Instagram advertisements that are associated with Donald Trump’s and Joe Biden’s official Facebook pages. Our 2020 dashboard uses data from the Facebook Ad Library to visualize weekly aggregations about the candidates’ advertisement messaging using our own classifiers, in addition to aggregated spending, impression, and demographic data provided by Facebook.

We aimed to expand the project to include PACs, Super PACs, and other advertising for or against the presidential candidates. In expanding our analysis, the Illuminating team identified critical flaws with Facebook’s Ad Library that challenge our ability to make transparent the scope and nature of advertising around the 2020 U.S. presidential election. Before we review these problems, we offer a brief description of the Ad Library’s purpose and structure.

Facebook Ad Library

Facebook introduced its Ad Library in 2018. The company describes it as a tool that “provides advertising transparency by offering a comprehensive, searchable collection of all ads currently running from across Facebook apps and services, including Instagram.” The site contains copies of ads that ran on Facebook and Instagram on or after May 7, 2018. Ads are organized into several categories. This report focuses on ads categorized as “social issues, elections or politics” (also referred to as “issues, elections, or politics”). Facebook’s Help Center states that ads must be classified as “social issues, elections or politics” if they fit any of the following criteria:

- They’re made by (or on behalf of), or about a candidate running for public office, a political figure, a political party or advocates for the outcome of an election to public office.

- They’re about any election, referendum, or ballot initiative, including “go out and vote” or election campaigns.

- They’re about social issues in the location where the ad is placed. Learn more about what we consider to be ads about social issues.

- They’re regulated as political advertising.

Source: “How are ads about social issues, elections and politics identified on Facebook?” from Facebook’s Help Center

The Ad Library’s website includes two tools that can be used to access individual ads and aggregated summary information. First, the Ad Library itself (or the “archive”) lets users search for ads by keyword or advertiser name and refine their searches using filters. Second, the Ad Library Report provides aggregated, sortable, and searchable data about advertisers’ spending behaviors.

For users who wish to collect and analyze large volumes of data, Facebook offers two additional resources: its Ad Library API, and its Graph API Explorer, which provides an online interface that developers can use to query Facebook’s API (including the Ad Library API). Given the systematic nature of the issues we have discovered using the Ad Library, the following report refers to — and includes examples from — the library’s archive, report, and API.

It should be noted that critics of current digital advertising practices have identified legislative loopholes that allow advertisers to conceal, misrepresent, or fail to disclose their identities. Consequently, digital election ads may run online without ever being identified as such. This problem is endemic to the broader digital advertising landscape, but the shortcomings of Facebook Ad Library are nevertheless embedded within this broader set of issues.

1: Advertiser Data

A central focus of campaign advertising research is spending information: Who are the most active advertisers in an election cycle? Are advertisers meeting the FEC’s legal requirements for political advertising? What are advertisers saying in their ads? Answering questions such as these requires accurate information about advertisers; gaps in advertiser data limit the depth of analysis that researchers can perform.

Facebook’s advertiser information needs to be understood in terms of funding entities and pages.

A funding entity is the organization or individual that buys a political ad. The funding entity appears in the ad as a “disclaimer” on the website or “byline” on the API. All ads that relate to “social issues, elections or politics” must include a disclaimer statement.

Section 10.b of Facebook’s advertising policies details the requirements for disclaimers. It states that advertisement disclaimers must:

- accurately represent the name of the entity or person responsible for the ad.

- not include URLs or acronyms, unless URLs or acronyms make up the name of the organization, which must also be accurately reflected on the website provided.

- not include “Paid for by” or similar language that duplicates language provided by Facebook.

Source: Section 10.b, “Disclaimers for Ads About Social Issues, Elections or Politics,” from Facebook’s Advertising Policies.

Advertisers also must choose a Facebook page to associate their ad with, and it must be a page that the advertiser has administrative rights to. Although ads must be associated with a page, they only appear on targeted users’ news feeds—that is, ads do not appear as posts on the advertiser’s Facebook page. The advertisement’s disclaimer is listed next to its page name on targeted users’ feeds.

Even with these requirements, it is challenging to determine who is running ads on Facebook. The disclaimer collection process lacks consistency; the Ad Library’s platform obfuscates disclaimer information; and both the platform and API limit users’ ability to identify and track certain funding entities. We detail these issues in depth below.

1.1 Naming inconsistencies

While advertisers are required to provide a disclaimer, there is no standardized format that they are legally required to adhere to. In the example below, each disclaimer references the same advertiser:

| Page Name | Disclaimer |

|---|---|

| Cost of Chaos | Priorities USA Action. 202-455-8428. Not authorized by any candidate or candidate’s committee. |

| Let’s Be Honest | Priorities USA |

| North Carolina Before Party | Priorities USA and Majority Forward |

| Here For This | Priorities USA Action. 202-904-0620. Not authorized by any candidate or candidate’s committee. |

| Working For Us | Priorities USA Action and SMP. (302) 469-3772. (202) 871-9255. Not authorized by any candidate or candidate’s committee. |

| Priorities USA Action | Priorities USA Action |

| Priorities USA Action | Priorities USA Action. Not authorized by any candidate or candidate’s committee. |

| For Michigan’s Future | Priorities USA and For Our Future Action Fund |

| Florida Knows Best | Priorities USA Action and Senate Majority PAC. Not authorized by any candidate or candidate’s committee. |

Each of these disclaimers lists Priorities USA Action as a funder or co-funder, but the disclaimers’ descriptions of Priorities USA Action are inconsistent.

Nebulous and inconsistent disclaimer names become problematic when trying to locate ads purchased by a specific funding entity. Our search for “Priorities USA” returned a total of 47 page/disclaimer combinations; if we had searched the PAC’s full name, “Priorities USA Action,” our search would have only returned 30 page/disclaimer combinations.

Even more problematic are cases when the advertiser’s disclaimer is insufficient to identify exactly who is purchasing the ad. For example, the disclaimers below share similar enough names that it is unclear which specific organization(s) they are referring to:

| Page Name | Disclaimer |

|---|---|

| We The People | We The People |

| Unite the People | We the People Org, Inc. |

| We The People – Pennsylvania Action | We The People – PA Action |

| We The People – Pennsylvania | We The People – PA |

| We The People | We the People CT |

| We The People Convention | We The People Convention |

| Vote November 3rd | We The People Action Fund, using regulated funds |

| WE The PPL | We The People Products |

| We the People Summit | We the People. Not authorized by a candidate or committee. |

Users may be able to verify some advertisers’ identities by cross-referencing a disclaimer’s content with publicly-available forms. However, the manual verification process carries the risk of human error and does not always produce clear answers.

Further, this strategy does not scale. There are 113,932 unique disclaimers in Facebook’s Ad Library as of 3 October 2020, many of which contain ambiguities like the examples above. Given how expansive and inconsistent this data is, the resources required to manually check each disclaimer can be prohibitive.

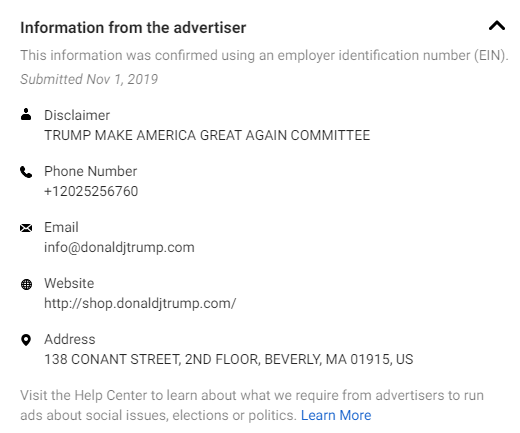

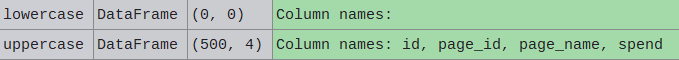

Additional challenges surface when searching for disclaimers with Facebook’s API, which requires case-sensitive and punctuation-sensitive disclaimer queries. For instance, querying “trump make america great again committee” (lowercase) instead of “TRUMP MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN COMMITTEE” (uppercase) returns 0 results:

As the above example demonstrates, querying one version of a disclaimer will not yield results for the other. Biden’s and Trump’s campaigns have both run multiple variations of several disclaimers:

| Page Name | Disclaimer |

|---|---|

| Donald J. Trump | TRUMP MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN COMMITTEE |

| Donald J. Trump | DONALD J. TRUMP FOR PRESIDENT, INC. |

| Donald J. Trump | the Trump Make America Great Again Committee |

| Donald J. Trump | Donald J. Trump for President, Inc. |

| Donald J. Trump | These ads ran without a disclaimer |

| Joe Biden | BIDEN VICTORY FUND |

| Joe Biden | BIDEN FOR PRESIDENT |

| Joe Biden | Biden for President |

| Joe Biden | American Possibilities PAC |

| Joe Biden | American Possibilities, not authorized by any candidate or candidate’s committee |

To exhaustively collect all of the ads that these advertisers are running — not just on Trump’s and Biden’s official pages, but across any other affiliated pages — at least ten different disclaimer queries are currently required. Constant vigilance also is needed to build additional queries as new names or variations surface.

1.2 Missing information

Facebook’s documentation on disclaimers states that all advertisements about “social issues, elections or politics” require a disclaimer. Nevertheless, there are multiple documented cases of ads that ran without a disclaimer.

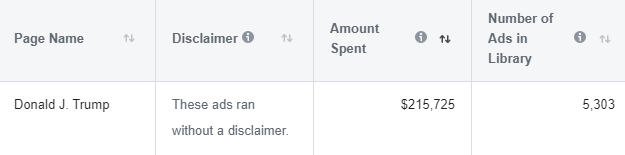

For instance, as of 3 October 2020, Facebook’s Ad Library Report notes that 5,303 ads ran on Trump’s official campaign Facebook page without a disclaimer since 2018. (This copy of Facebook’s Ad Library Report does not contain any ads on Biden’s official campaign page that have run without a disclaimer.) There is no explanation as to why the Trump campaign was able to run ads without a disclaimer.

Facebook’s documentation on disclaimers indicates that advertisers are allowed to edit and update their disclaimers. Although Facebook re-reviews any edits that are made, at the time of writing, this information is not updated on the platform in consistent ways.

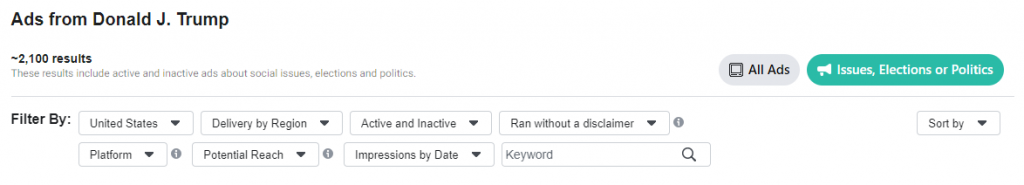

Although there are roughly 5,000 ads that ran on Donald Trump’s official page without a disclaimer, filtering his Ad Library page to show ads that “Ran without a disclaimer” displays only ~2,100 ads.

Some of these ads list disclaimers that were presumably added retrospectively. However, we do not know at which point these disclaimers were added, nor do we know how many impressions the ads obtained before the disclaimer was added.

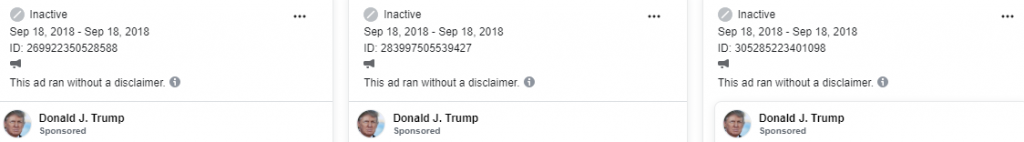

A review of Trump’s Ad Library page indicates that some ads — despite accruing impressions and being stored in the “social issues, elections or politics” category — still do not have disclaimers:

In cases such as these, researchers or journalists have no way to know who purchased the ads and whether the advertiser(s) ran ads on any other page(s).

To further investigate how pervasive “These ads ran without a disclaimer” statements are in the Ad Library, we conducted a deeper investigation Between 7 May 2018 and 3 October 2020, our analysis found:

- 147,042 unique page names with “this ad ran without a disclaimer” as their disclaimer

- 733,808 ads across these pages ran without a disclaimer

- $62,435,602 USD spent on social issues, elections, or politics ads that ran without disclaimers

It is encouraging to see that Facebook is requiring ads that have been retrospectively classified as being about social issues, elections or politics to include a disclaimer in the Ad Library, yet our analysis suggests that this approach has not been effectively applied across the board as there are still political ads in the library missing disclaimers.

2: Inaccessible Information & Data

Effective advertising transparency requires a robust and organized documentation system that actively mitigates inconsistencies, and that makes an effort to communicate changes or updates to its users. Our research indicates that there is an absence of easily retrievable documentation of Facebook’s Ad Library, Report, and API.

2.1 Unannounced updates

To date, we have not been able to identify any centralized location on Facebook that provides and archives announcements about changes to Facebook’s Ad Library, Report, and API. Instead, we discover changes and updates by happening upon them or when news outlets cover policy changes.

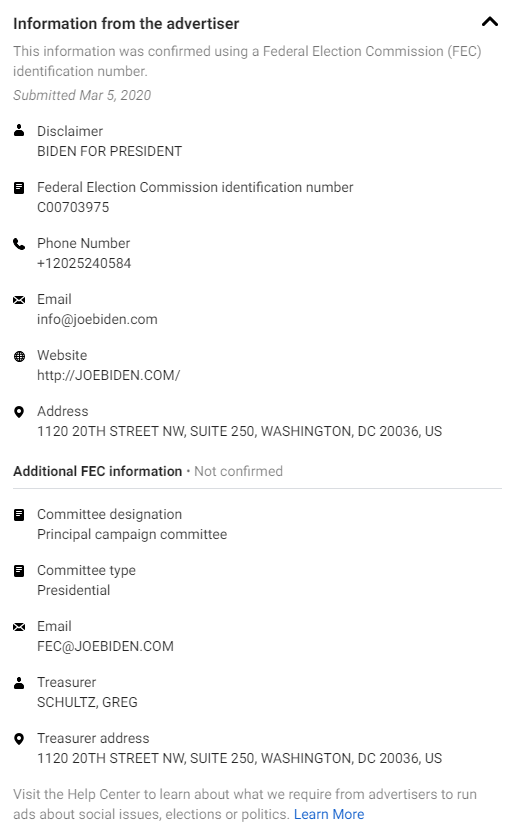

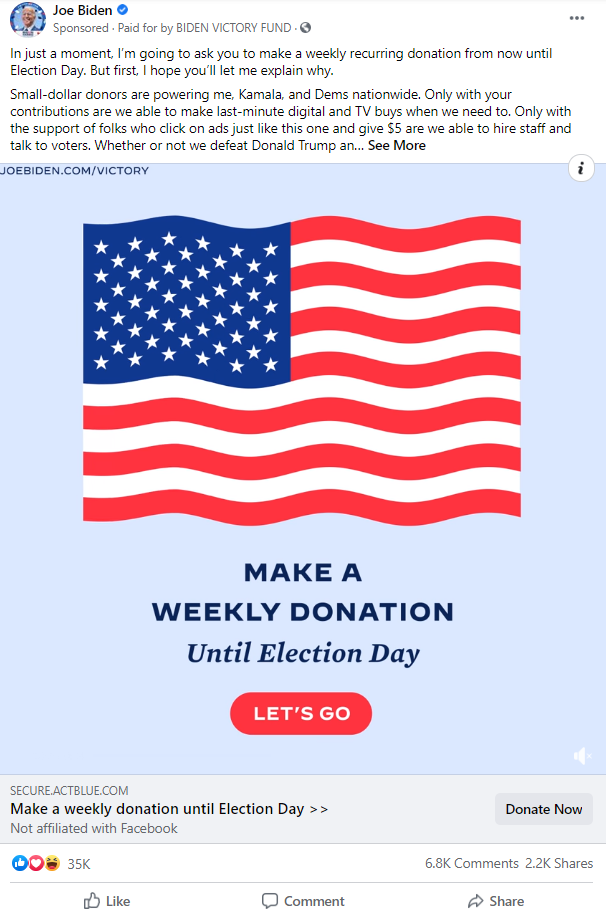

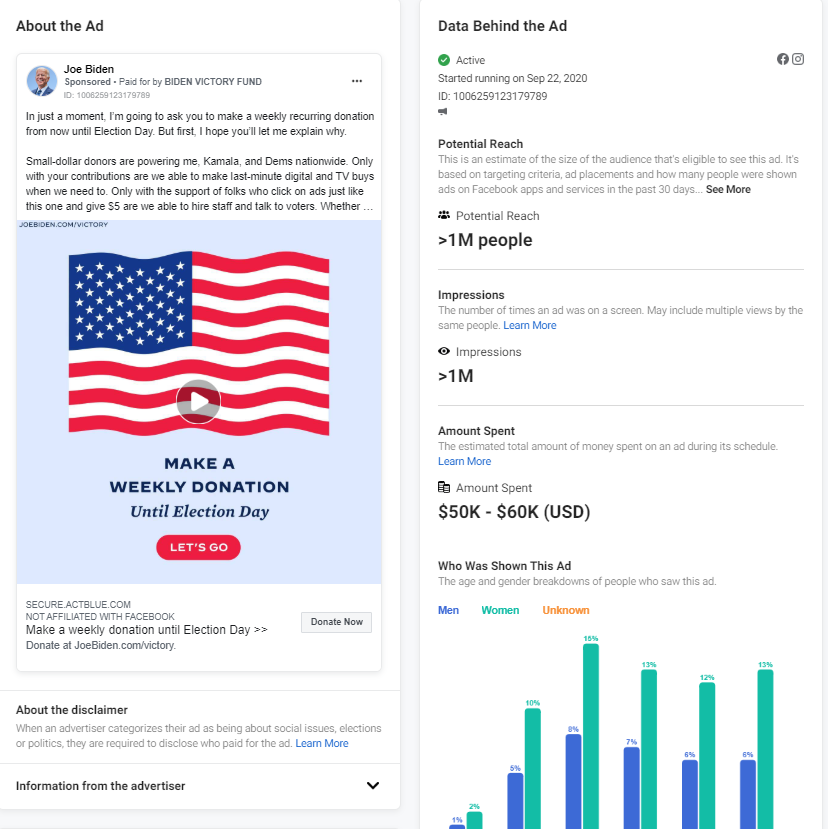

For instance, we have recently noticed that some advertisements in the Ad Library now display additional verification details that an advertiser has provided, such as FEC and/or contact information. This content appears in a given ad’s “Information from the advertiser” section:

This information does not indicate when changes occurred. This update does not appear to have been retrospectively applied to older ads that use the same disclaimer.

Other unannounced changes include: the addition of cards at the top of advertisers’ pages that display a list of pages that share overlapping advertiser information with the active page; an update that allows users to filter their search results based on whether an ad has received impressions during a specific date or time range (rather than preset categories, such as the past 1, 7, 30, 60, or 90 days); and the addition of date fields to the Ad Library API’s search parameters.

It could be that we were not paying attention to the proper channels when Facebook made these announcements, but without an easily accessible archive, it is impossible for researchers to compose a timeline of when certain changes were implemented. We are therefore unable to confidently identify errors or discrepancies in the information that the Ad Library and API are supposed to provide at any moment.

2.2 Inaccessible data

There are types of information that Facebook stores on advertisements but does not make publicly available within the Ad Library and/or its API.

For instance, advertiser verification information is available for individual ads, but it is not available to collect through the API. Consequently, we cannot analyze advertisers’ additional verification details at scale.

Another critical, but inaccessible piece of information is ad engagement metrics (e.g., reactions, shares, comments). Users are allowed to react to, share, and comment on ads that appear on their newsfeeds, but researchers and journalists do not have access to any engagement metrics through the Ad Library and API.

Having data on reactions, shares, and numbers of comments would make transparent the potential effect and spread of ads.

Without access to engagement data through the Ad Library or the API, it becomes extremely difficult for researchers and journalists to investigate evidence of manipulation of likes and shares; who shares content; whether shared content receives additional reactions; and the extent to which misinformation and disinformation circulate in advertisements’ comments. Given a recent whistleblower memo from a Facebook employee who alleges that her team removed “10.5 million fake reactions and fans from high-profile politicians in Brazil and the US in the 2018 elections,” our concerns are warranted

2.3 Hard-to-find information

When navigating Facebook’s documentation, we fell down a rabbit hole of links of varying relevance. Information about the Ad Library, including its policies, are dispersed across the Ad Library itself, Facebook’s Business Help Center, Facebook’s Help Center, and a unique hub that describes Facebook’s Advertising Policies. Within each of these sources, information is typically dispersed across multiple pages, making it challenging to systematically verify the consistency of the information found within each resource.

For example, Facebook’s advertising policies are not directly linked anywhere on the Ad Library’s landing page. At the bottom of the landing page is a link called “Terms,” but this link redirects to Facebook’s main privacy landing page, rather than its Advertising Policies.

To date, the only time our researchers have seen a direct link to the Ad Library’s policies within the Ad Library itself is in the statement that appears on content that has been removed.

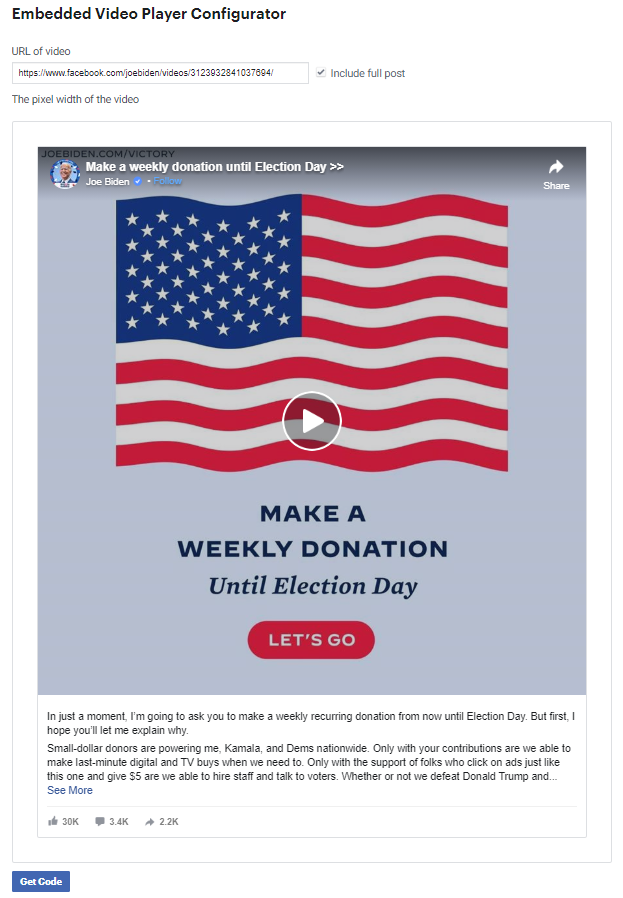

Finding consistent information can also be challenging for advertisements that appear directly on a user’s news feed. At the time of this writing, when an ad appears on a user’s news feed, it does not contain any links to the copy of the ad that is stored in the library. Users can access a stable URL for the ad by opening its embed code, such as in the example below:

However, the ad’s link contains a post ID — rather than an ad ID. Searching for the ad in the Ad Library with its post ID returns the following message:

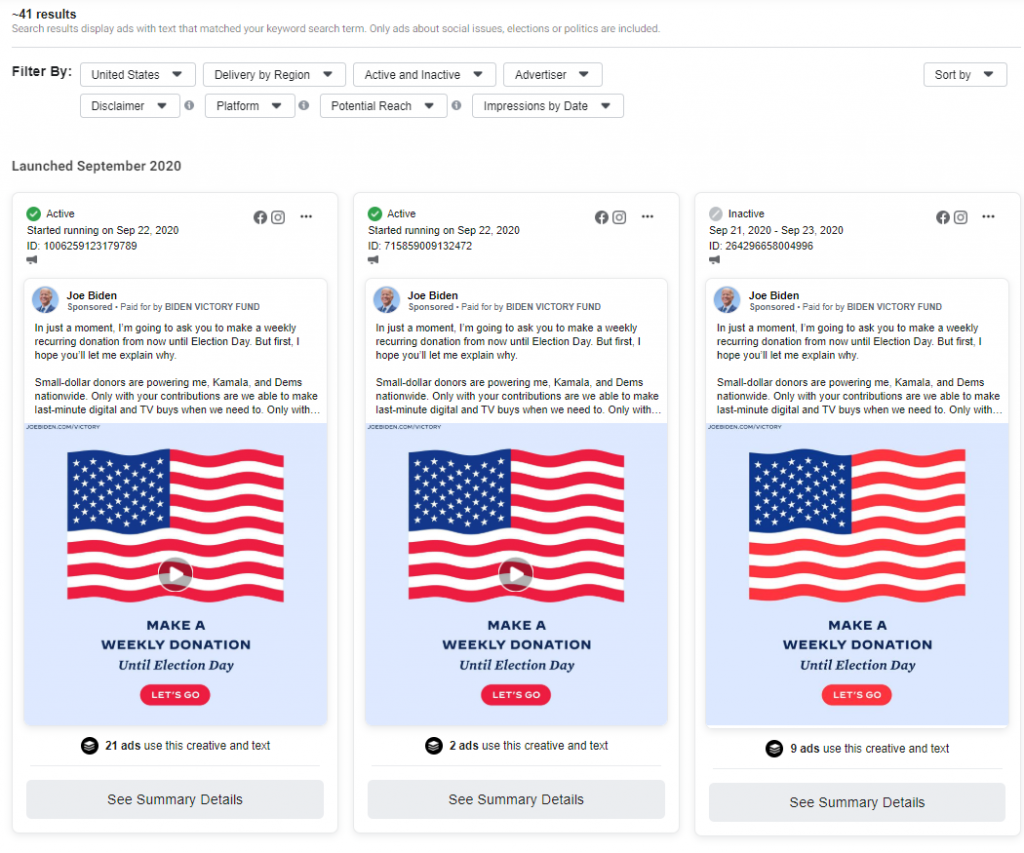

Searching for the ad’s text in the Ad Library returns 41 copies of the ad, clustered in four groups within the Ad Library search results. However, none of these ads share an ID with the copy of the ad that appears on users’ news feeds:

It is unclear whether the copy of the ad from the user’s news feed corresponds with one of the 41 copies of the ad in the Ad Library, or if it is has not yet been added. This obfuscation reduces the ability for Facebook users to learn more about how they are being targeted by advertisers.

Ad ID discrepancies, unannounced changes to the Ad Library platform, sprawling documentation, and incomplete pages make it difficult for researchers and journalists to find accurate and up-to-date information about the Ad Library. Ultimately, the disorganized nature of Facebook’s Ad Library documentation risks exacerbating, rather than mitigating, ongoing concerns about the library’s lack of transparency.

3: Policy & Enforcement

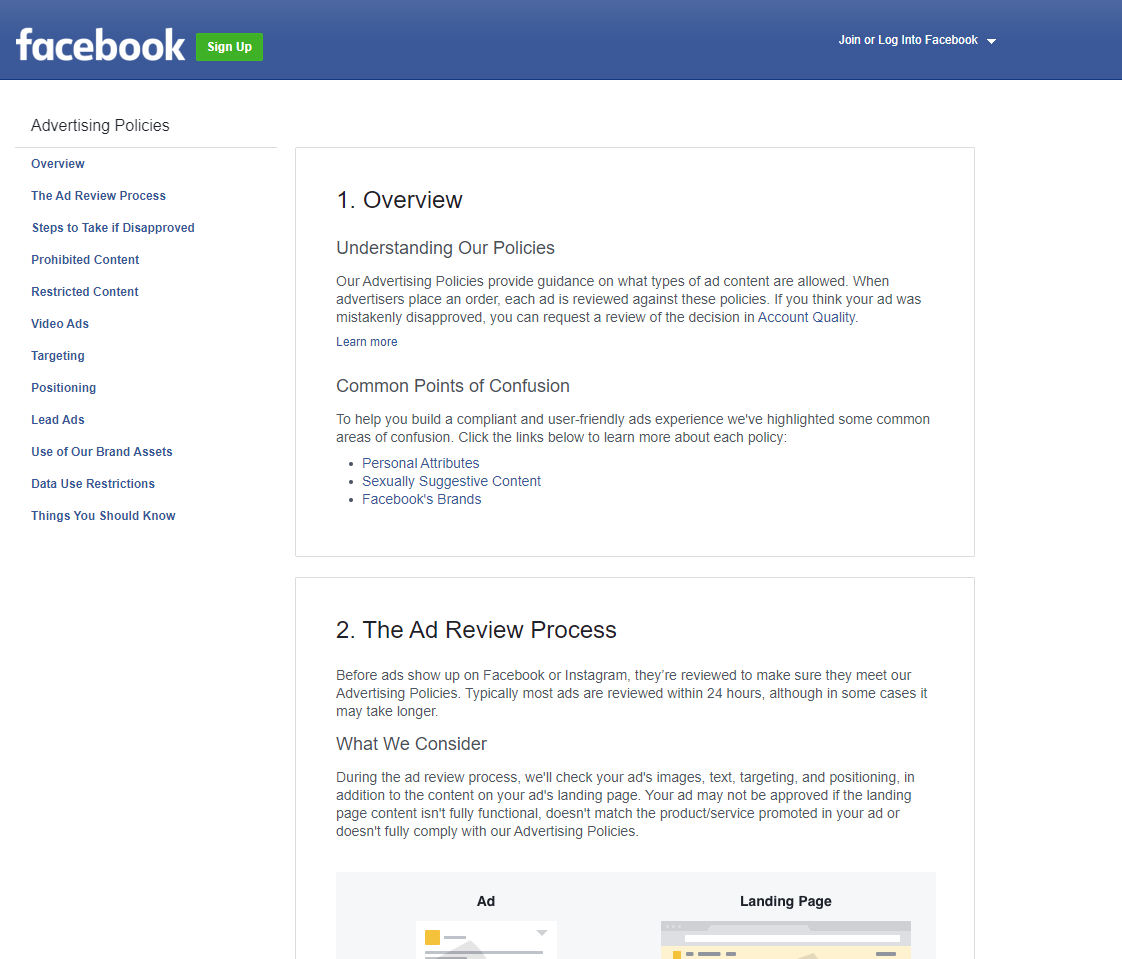

Advertisers are required to adhere to Facebook’s platform and advertising policies. Facebook’s advertising policy contains twelve sections that detail the ad review process, describe which content is prohibited and/or restricted, and outline the steps that advertisers can take to appeal an advertisement’s removal from the platform. Some of the categories and subcategories include ‘learn more’ hyperlinks that outline the rules in more detail, while others redirect to broader sets of Facebook policies (i.e., rules applying to the platform writ large).

3.1 Policy ambiguity

Within the Advertising Policies document, section 5, subsections 10.a and 10.b, detail policies that are specific to “Ads About Social Issues, Elections or Politics.” Subsection 10.a clarifies what constitutes an ad about ‘social issues, elections or politics’ and notes that ads meeting these criteria are required to adhere to “applicable laws and regulations” and “regardless of location.” Facebook provides examples, such as “blackout periods” and “foreign interference,” but it does not cite any specific laws or regulations.

It is unclear whether “applicable laws and regulations” are defined as U.S. campaign laws, the laws that are specific to the country/countries in which advertisements are being run, the laws that are specific to the country in which an election is taking place, or a different scope altogether. In short, Facebook’s policies regarding ads about “social issues, elections or politics” are ambiguous about the specific laws that advertisers are required to follow.

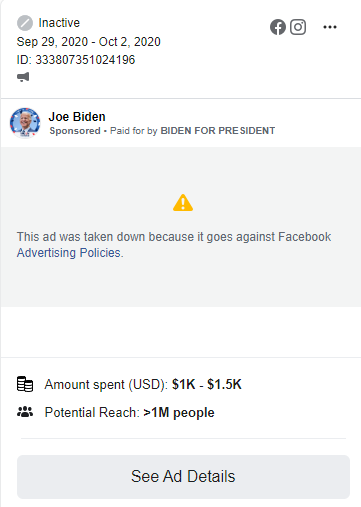

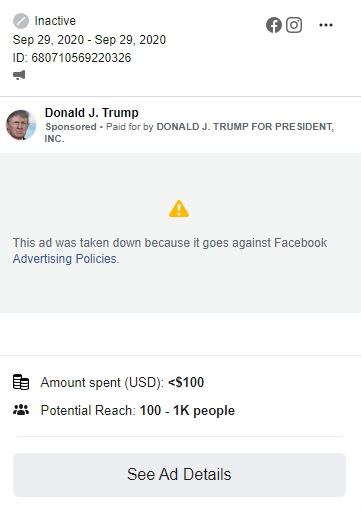

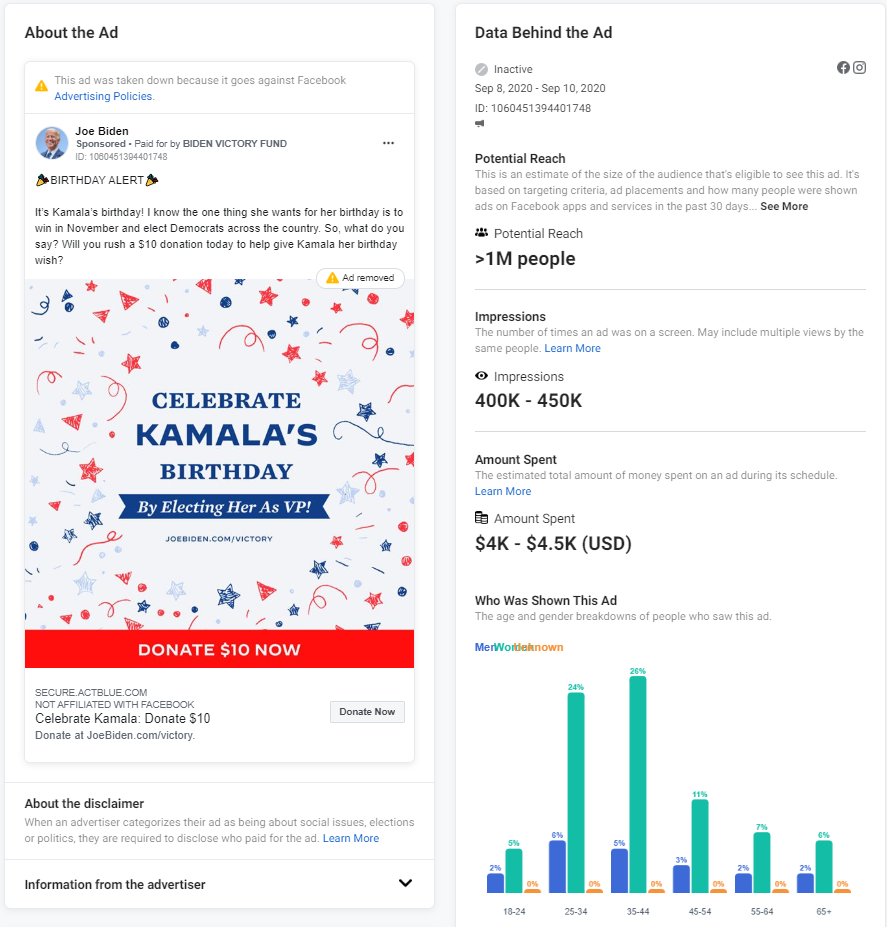

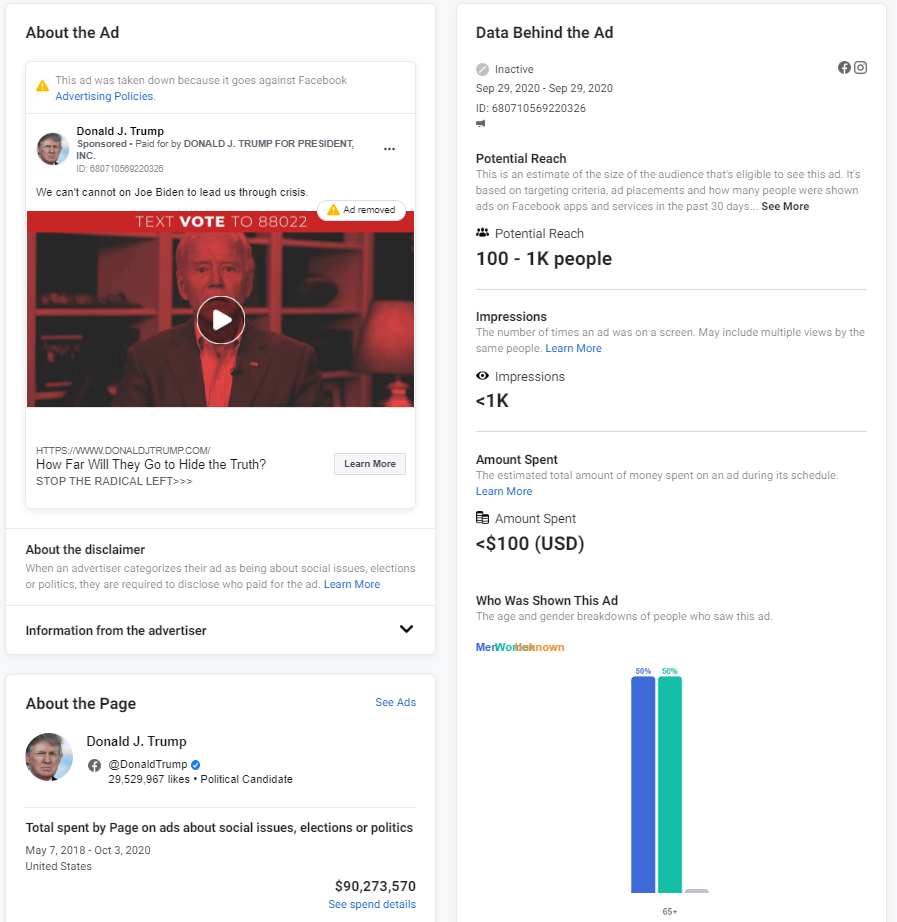

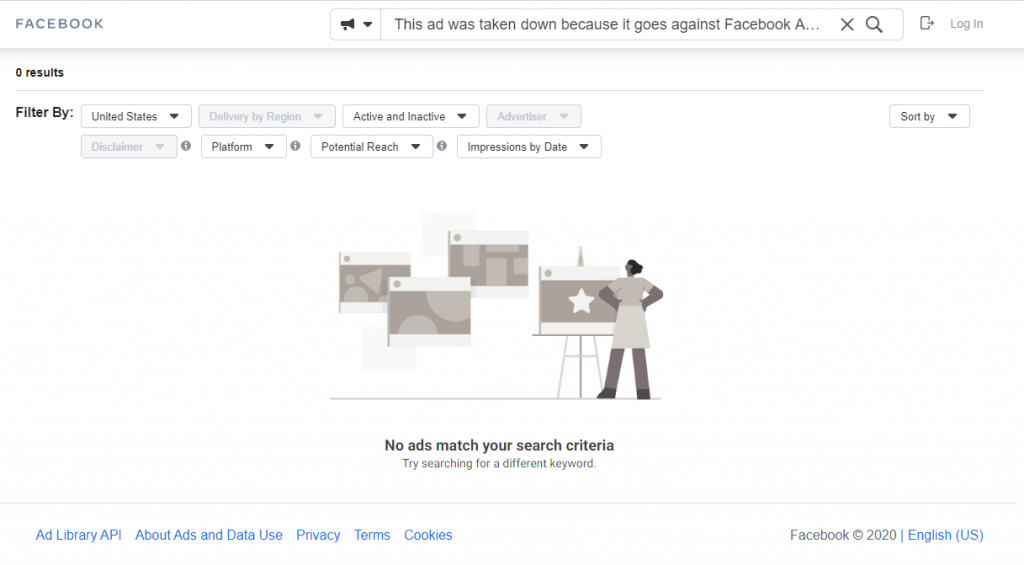

Similarly ambiguous are the reasons for advertisement removals. Facebook reserves the authority to remove ads from circulation that the platform later discovers violate their advertising policies. When we search for an ad in the Ad Library that Facebook has removed: the following statement appears: “This ad was taken down because it goes against Facebook Advertising Policies.”

The button underneath the ad that says “see ad details” provides a view of the original version of the ad, as well as information about its cost and reach (prior to removal).

The Ad Library provides no information about why an ad was removed. The hyperlink in the removal statement directs users to section 5 of Facebook’s Advertising Policies, which outlines thirteen types of restricted content, including ads for alcohol or real money gambling that do not comply with local laws or industry codes, weight loss products targeted at people under 18, or “social issues, elections or politics” ads that do not comply with applicable laws and Facebook policies.

In some instances, researchers and journalists may be able to intuit from an ad’s image and/or text which policy or policies the ad has violated. However, the reason(s) for removal are not always immediately apparent, and even when they are, there is no guarantee that inferences are accurate. For the removed ad we’ve shared above as an example, our team carefully reviewed section 5 of Facebook’s Advertising Policies, but could not identify which of the 13 types of restricted content the ad included.

3.2 Inability to track enforcement

Like other aspects of the Ad Library, the ability to view removed ads does not scale. Facebook’s Ad Library platform and API do not allow users to query removed ads. Text searches that use the language from the cover of removed ads (“This ad was taken down because it goes against Facebook Advertising Policies”) do not systematically return removed content:

Short of manually reviewing each ad from each individual page in the archive, users have no way of knowing the total number of removed ads, which pages or disclaimers are associated with removals, how long an ad typically ran before removal, or why an ad was removed. For researchers and journalists investigating political advertising, there is no systematic approach available to evaluate whether certain violations are enforced more or less frequently than others, nor is there a way to determine whether policies are enforced equally and consistently across advertisers.

The overall scope of policy violations and policy enforcement, in short, is nearly impossible to assess without access to data about which advertisements have been removed and the reason(s).

Recommendations

Given the challenges we encountered in our efforts to make transparent political advertising expenditures and messaging, we propose the following changes in FB’s advertising policies:

- Facebook should require the advertiser to include in their disclaimer their full, legal name on all ad campaigns. Moreover, disclaimers should be hyperlinked back to either a public-facing website of the organization or the organization’s Facebook page to assist with disambiguating organizations with similar names. The search function should not be case or punctuation sensitive.

- Facebook should not be running ads that are missing a disclaimer. When an advertiser becomes authorized to run ads on “social issues, elections or politics,” the ads that they have purchased must be retroactively updated to include the correct disclaimer to ensure transparency.

- Updates — be it to individual ads, platform features, API search/return fields, the Ad Library report, or Facebook’s Advertising Policies — should be labeled, dated, and easy to locate within the Ad Library’s website and documentation.

- When an ad is removed, the specific policy that it violated should be listed. The Ad Library Report should provide summary information about the number of ads that have been removed and the pages that removed ads ran on. Facebook’s Ad Library and API should include search and/or return fields to access removed ads.

- Facebook’s own policies and guidelines need to be routinely updated and more easily accessible for journalists and researchers. The lack of documentation and the vagueness of its policies open up loopholes for dark money and misinformation campaigns to exploit.

We appreciate that Facebook created the Ad Library Report and API to support visibility and surveillance of ads running on its platform that pertain to campaigns and elections. These additional measures would further the cause of transparency and assist researchers and journalists to hold our political elites accountable and ensure that the information environment is less prone to misinformation and voter manipulation.